Brown v. Board at 61

Posted On June 23, 2015

“Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments…It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today, it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment.”

– Chief Justice Earl Warren,

May 17, 1954

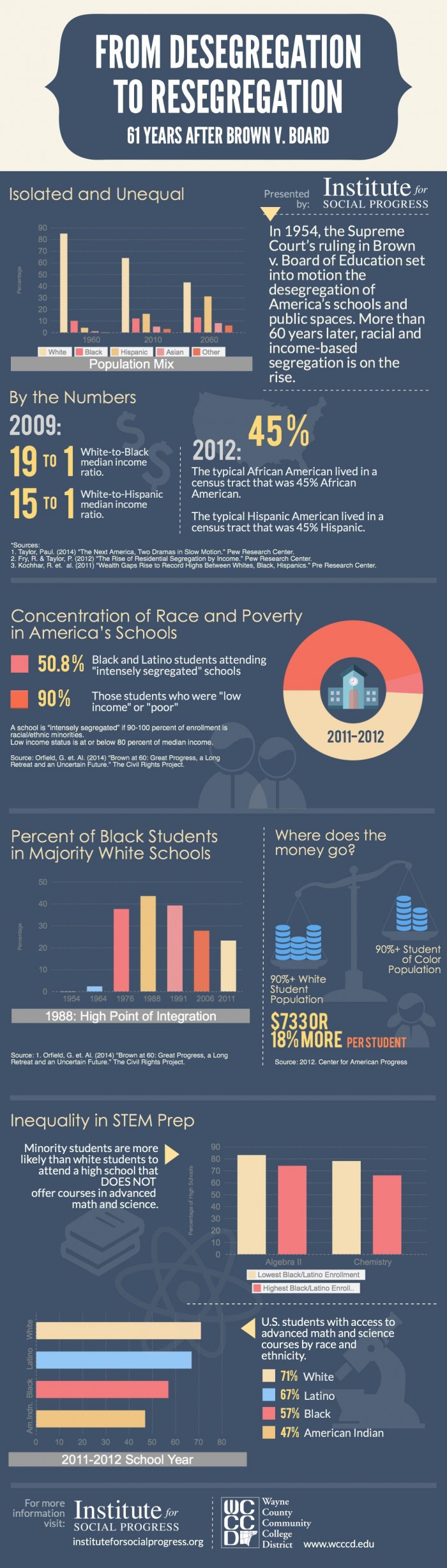

Over six decades have passed since the Warren Court rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine in public education, ruling that separate facilities “are inherently unequal” and detrimental to not only people of color, but to society as a whole. And while, as many legal scholars, historians, and theorists rightly point out,Brown was compromised almost as soon as it was adjudicated, the decision will forever represent a critical juncture at which the American justice system recognized and reaffirmed the importance of racial equality within the American experiment.

And so we revisit Brown on its May anniversary, not only out of respect for what it did – which was to provide a positive legal foundation for the desegregation of public space throughout the United States – but for the direction and guidance it can provide us today, namely how to understand and address the radical resegregation of public education occurring throughout low-income communities of color.

Consider the demographic shift our nation has undergone in recent decades. A Pew Research Center report published last year shows that, in 1960, the racial makeup of America was something like 85 percent white, 10 percent black, 4 percent Latino/a, and 1 percent Asian. In 2010, America was 64 percent white, 12 percent black, 16 percent Latino/a, 5 percent Asian, and 3 percent “other.” Last year was the first time in our nation’s history that white students were a minority in our schools.

Why this matters is that racial status and education (both access to education and educational outcomes) have long been linked in this country. We know that high-minority schools get less funding and have less-qualified teachers with higher turnover than low-minority schools. Moreover, minority students in high-minority schools are taught by teachers who usually don’t look like them, have less access to educational resources and are less likely to graduate than their peers in low-minority schools.

According to The Civil Rights Project (CRP) at UCLA, the U.S. is undergoing a “serious resegregation” of our schools, to levels not seen since the 1970s. In the aftermath of the 2007 ruling in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No.1, which signaled a dangerous return to a jurisprudence of colorblindness, the legal foundation of attempts at a more complete integration of our nation’s schools is under threat.

This finding casts a long shadow over another CRP report, just released in April of this year, that documents the positive results of recent racial integration efforts in Connecticut. The Connecticut case study provides not only evidence of the potential for racial integration to produce positive outcomes, but also a prescriptive framework to bypass the constraints imposed on the project of integration by Milliken v. Bradley. (Sheff v. O’Neill, the Connecticut case, found segregation to be against “the state’s law” and prompted the legislature to develop solutions to segregation and inequities in its schools.)

Brown is a reminder to look beyond “tangible factors” when considering racial equality in education; to acknowledge that though we may not see the consequences of segregation, this is exactly why we must act, and act quickly, to address the practice.

The fate of the future America is being decided today and tomorrow in classrooms across the country – we cannot afford to mortgage our nation’s future on inaction.